by Marian Tupy

Reason

December 13, 2016

Jonathan Haidt, the well-known psychologist from New York University, started as a "typical" liberal intellectual, but came to appreciate the awesome ability of free markets to improve the lives of the poor. Earlier this year, he penned an essay in which he pointed to what he called "the most important graph in the world." The graph reflected Angus Maddison's data showing a massive increase in wealth throughout the world over the last two centuries and which is reproduced, courtesy of Human Progress, below.

The "great enrichment" (Deirdre McCloskey's phrase) elicits different responses in different parts of the world, Haidt noted. "When I show this graph in Asia," Haidt writes, "the audiences love it, and seem to take it as an aspirational road map… But when I show this graph in Europe and North America, I often receive more ambivalent reactions. 'We can't just keep growing forever!' some say. 'We'll destroy the planet!' say others. These objections seem to come entirely from the political left, which has a history, stretching back centuries, of ambivalence or outright hostility to capitalism."

Haidt's experience mirrors my own. When giving talks about the benefits of free markets, audiences in Europe and America invariably note the supposedly finite nature of growth and express worry about the environmental state of the planet. Why? In Haidt's view, capitalist prosperity changes human conscience. In pre-industrial societies, people care about survival. "As societies get wealthier, life generally gets safer, not just due to reductions in disease, starvation, and vulnerability to natural disasters, but also due to reductions in political brutalization. People get rights."

More

This blog is dedicated to the worldwide struggle for freedom, individual liberties, personal autonomy and the right to self-ownership - against any kind of legal paternalism, legal moralism and authoritarianism. Its aim is to post related news and commentary published mainly in the major U.S., European and Greek media. It was created by Prof. Aristides Hatzis of the University of Athens.

Tuesday, December 13, 2016

Sunday, November 27, 2016

Ο Θάνατος ενός Δικτάτορα

του Αριστείδη Χατζή

Protagon

27 Νοεμβρίου 2016

Ο κόσμος απαλλάχθηκε από έναν δικτάτορα. Ο θάνατος ενός δικτάτορα, ιδιαίτερα ενός δικτάτορα που βρίσκεται, έστω και τυπικά, στην εξουσία είναι πάντα ένα πολύ καλό νέο. Αμέσως μετά τον θάνατο δικτατόρων το αυταρχικό τους καθεστώς κλονίζεται. Αυτό ελπίζουμε να γίνει και τώρα στην Κούβα.

Κανονικά θα έκλεινα το άρθρο εδώ. Τι άλλο να πούμε; Ας ευχηθούμε να απαλλαγεί σύντομα ο κουβανικός λαός κι από τον αδελφό και διάδοχό του.

Όμως όχι. Πρέπει να πούμε μερικά ακόμα πράγματα. Ο Κάστρο είναι ειδική περίπτωση.

Καταρχήν γιατί δεν ήταν ένας απλός δικτάτορας. Είναι ο μακροβιότερος δικτάτορας μεταπολεμικά. Κυβέρνησε αυταρχικά την Κούβα σχεδόν 57 χρόνια. Ας του αναγνωρίσουμε λοιπόν ότι είναι πρωταθλητής της καταπίεσης. Το ρεκόρ του δύσκολα θα σπάσει πλέον. Στην πινακοθήκη των τεράτων του 20ου αιώνα του ανήκει επάξια μια πρωταγωνιστική θέση.

Ο Κάστρο ήταν ένας τυπικός δικτάτορας. Κυβέρνησε αυταρχικά, καταδίωξε τους αντιπάλους του με αγριότητα, έβαψε τα χέρια του με άφθονο αίμα, διατήρησε το λαό του σε κατάσταση εξαθλίωσης ενώ ο ίδιος ζούσε μια ζωή μέσα στη χλιδή και στις κάθε είδους απολαύσεις, στήριξε συγγενή αυταρχικά καθεστώτα, εξασφάλισε την κληρονομική διαδοχή του και βέβαια δεν μετάνιωσε για κανένα από τα αναρίθμητα εγκλήματα που διέπραξε.

Η συνέχεια του άρθρου

Protagon

27 Νοεμβρίου 2016

Ο κόσμος απαλλάχθηκε από έναν δικτάτορα. Ο θάνατος ενός δικτάτορα, ιδιαίτερα ενός δικτάτορα που βρίσκεται, έστω και τυπικά, στην εξουσία είναι πάντα ένα πολύ καλό νέο. Αμέσως μετά τον θάνατο δικτατόρων το αυταρχικό τους καθεστώς κλονίζεται. Αυτό ελπίζουμε να γίνει και τώρα στην Κούβα.

Κανονικά θα έκλεινα το άρθρο εδώ. Τι άλλο να πούμε; Ας ευχηθούμε να απαλλαγεί σύντομα ο κουβανικός λαός κι από τον αδελφό και διάδοχό του.

Όμως όχι. Πρέπει να πούμε μερικά ακόμα πράγματα. Ο Κάστρο είναι ειδική περίπτωση.

Καταρχήν γιατί δεν ήταν ένας απλός δικτάτορας. Είναι ο μακροβιότερος δικτάτορας μεταπολεμικά. Κυβέρνησε αυταρχικά την Κούβα σχεδόν 57 χρόνια. Ας του αναγνωρίσουμε λοιπόν ότι είναι πρωταθλητής της καταπίεσης. Το ρεκόρ του δύσκολα θα σπάσει πλέον. Στην πινακοθήκη των τεράτων του 20ου αιώνα του ανήκει επάξια μια πρωταγωνιστική θέση.

Ο Κάστρο ήταν ένας τυπικός δικτάτορας. Κυβέρνησε αυταρχικά, καταδίωξε τους αντιπάλους του με αγριότητα, έβαψε τα χέρια του με άφθονο αίμα, διατήρησε το λαό του σε κατάσταση εξαθλίωσης ενώ ο ίδιος ζούσε μια ζωή μέσα στη χλιδή και στις κάθε είδους απολαύσεις, στήριξε συγγενή αυταρχικά καθεστώτα, εξασφάλισε την κληρονομική διαδοχή του και βέβαια δεν μετάνιωσε για κανένα από τα αναρίθμητα εγκλήματα που διέπραξε.

Η συνέχεια του άρθρου

Sunday, September 4, 2016

The Formula for a Richer World? Equality, Liberty, Justice

by Deirdre N. McCloskey

New York Times

September 2, 2016

The world is rich and will become still richer. Quit worrying.

Not all of us are rich yet, of course. A billion or so people on the planet drag along on the equivalent of $3 a day or less. But as recently as 1800, almost everybody did.

The Great Enrichment began in 17th-century Holland. By the 18th century, it had moved to England, Scotland and the American colonies, and now it has spread to much of the rest of the world.

Economists and historians agree on its startling magnitude: By 2010, the average daily income in a wide range of countries, including Japan, the United States, Botswana and Brazil, had soared 1,000 to 3,000 percent over the levels of 1800. People moved from tents and mud huts to split-levels and city condominiums, from waterborne diseases to 80-year life spans, from ignorance to literacy.

You might think the rich have become richer and the poor even poorer. But by the standard of basic comfort in essentials, the poorest people on the planet have gained the most. In places like Ireland, Singapore, Finland and Italy, even people who are relatively poor have adequate food, education, lodging and medical care — none of which their ancestors had. Not remotely.

More

New York Times

September 2, 2016

The world is rich and will become still richer. Quit worrying.

Not all of us are rich yet, of course. A billion or so people on the planet drag along on the equivalent of $3 a day or less. But as recently as 1800, almost everybody did.

The Great Enrichment began in 17th-century Holland. By the 18th century, it had moved to England, Scotland and the American colonies, and now it has spread to much of the rest of the world.

Economists and historians agree on its startling magnitude: By 2010, the average daily income in a wide range of countries, including Japan, the United States, Botswana and Brazil, had soared 1,000 to 3,000 percent over the levels of 1800. People moved from tents and mud huts to split-levels and city condominiums, from waterborne diseases to 80-year life spans, from ignorance to literacy.

You might think the rich have become richer and the poor even poorer. But by the standard of basic comfort in essentials, the poorest people on the planet have gained the most. In places like Ireland, Singapore, Finland and Italy, even people who are relatively poor have adequate food, education, lodging and medical care — none of which their ancestors had. Not remotely.

More

Tuesday, July 19, 2016

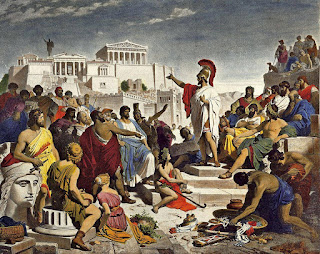

The Illiberal Democracy of Ancient Athens

by Aristides N. Hatzis

University of Athens

July 15, 2016

Abstract

Ancient Athenians introduced democracy, majoritarianism and popular sovereignty. They also introduced populism and rent-seeking. Moreover, Athenians didn’t invent the rule of law. The power of demos was almost unlimited, there were no constitutional guarantees, checks and balances. The laws were subjected to the whims of the majority of citizens or judges. Most importantly, individual rights were not recognized in Athens. The concept of liberty in Ancient Athens was very different from the concept of liberty that prevailed after the Great Revolutions of the late 18th and the early 19th century which led to the contemporary liberal democracies. We will discuss these issues with reference to famous historical episodes and trials. However, we will also see that the liberal ideas of individuality, toleration and the rule of law, appeared in a not-so-embryonic way, in three important works of the period (a tragedy, a comedy and a history book). These ideas were remarkably original but at the same time marginal. They didn’t exert any significant influence on the Athenian democratic institutions.

This is the text of a Keynote Lecture at the international conference: “Ancient Greece and the Modern World: The Influence of Greek Thought on Philosophy, Science and Technology” (Ancient Olympia, August 2016)

Download the Lecture (PDF)

University of Athens

July 15, 2016

Abstract

Ancient Athenians introduced democracy, majoritarianism and popular sovereignty. They also introduced populism and rent-seeking. Moreover, Athenians didn’t invent the rule of law. The power of demos was almost unlimited, there were no constitutional guarantees, checks and balances. The laws were subjected to the whims of the majority of citizens or judges. Most importantly, individual rights were not recognized in Athens. The concept of liberty in Ancient Athens was very different from the concept of liberty that prevailed after the Great Revolutions of the late 18th and the early 19th century which led to the contemporary liberal democracies. We will discuss these issues with reference to famous historical episodes and trials. However, we will also see that the liberal ideas of individuality, toleration and the rule of law, appeared in a not-so-embryonic way, in three important works of the period (a tragedy, a comedy and a history book). These ideas were remarkably original but at the same time marginal. They didn’t exert any significant influence on the Athenian democratic institutions.

This is the text of a Keynote Lecture at the international conference: “Ancient Greece and the Modern World: The Influence of Greek Thought on Philosophy, Science and Technology” (Ancient Olympia, August 2016)

Download the Lecture (PDF)

Tuesday, January 26, 2016

Political Freedom On the Rise Around the World Despite Naysayers

by Marian Tupy

Reason

January 26, 2016

Listening to the GOP presidential candidates, you would think that humanity is sprinting toward the gates of hell. What's needed, the talking heads on TV maintain, is a strong leader to set the world right. But, the world is already on the mend—irrespective of the actions of the megalomaniacal narcissist in the Oval Office today or the megalomaniacal narcissist poised to replace him in January 2017.

In recent years, plenty of commentators expressed concerns about the future of political freedom. As late as last year, Freedom House's "Freedom in the World" survey found that autocrats "now increasingly flout democratic values, argue for the superiority of what amounts to one-party rule, and seek to throw off the constraints of fundamental diplomatic principles."

What a difference a year makes!

In the America's, Argentina and Venezuela stepped back from the precipice. Far from being a vanguard of autocratic renaissance, Cuba is once again isolated as the hemisphere's sole full-fledged dictatorship. Africa and the Middle East remain, as ever, a bloody mess. Still, Nigeria, Africa's largest economy and most populous country (there will be more Nigerians in 2050 than Americans), saw a peaceful and largely free election that, for the first time, transferred power to an opposition candidate. Finally, the luster came off China and Russia—two countries that so many would-be autocrats pointed to as alternative models of political and economic development.

More

Reason

January 26, 2016

Listening to the GOP presidential candidates, you would think that humanity is sprinting toward the gates of hell. What's needed, the talking heads on TV maintain, is a strong leader to set the world right. But, the world is already on the mend—irrespective of the actions of the megalomaniacal narcissist in the Oval Office today or the megalomaniacal narcissist poised to replace him in January 2017.

In recent years, plenty of commentators expressed concerns about the future of political freedom. As late as last year, Freedom House's "Freedom in the World" survey found that autocrats "now increasingly flout democratic values, argue for the superiority of what amounts to one-party rule, and seek to throw off the constraints of fundamental diplomatic principles."

What a difference a year makes!

In the America's, Argentina and Venezuela stepped back from the precipice. Far from being a vanguard of autocratic renaissance, Cuba is once again isolated as the hemisphere's sole full-fledged dictatorship. Africa and the Middle East remain, as ever, a bloody mess. Still, Nigeria, Africa's largest economy and most populous country (there will be more Nigerians in 2050 than Americans), saw a peaceful and largely free election that, for the first time, transferred power to an opposition candidate. Finally, the luster came off China and Russia—two countries that so many would-be autocrats pointed to as alternative models of political and economic development.

More

Tuesday, January 12, 2016

Humans Innovate Their Way Out of Scarcity

by Marian Tupy

Reason

January 12, 2016

Last week, the World Bank updated its commodity database, which tracks the price of commodities going back to 1960. Over the last 55 years, the world's population has increased by 143 percent. Over the same time period, real average annual per capita income in the world rose by 163 percent. What happened to the price of commodities?

Out of the 15 indexes measured by the World Bank, 10 fell below their 1960 levels. The indexes that experienced absolute decline included the entire non-energy commodity group (-20 percent), agricultural index (-26 percent), beverages (-32 percent), food (-22 percent), oils and minerals (-32 percent), grains or cereals (-32 percent), raw materials (-32 percent), "other" raw materials (-56 percent), metals and minerals (-4 percent) and base metals (-3 percent).

Five indexes rose in price between 1960 and 2015. However, only two indexes, energy and precious metals, increased more than income, appreciating 451 percent and 402 percent respectively. Three indexes increased less than income. They included "other" food (7 percent), timber (7 percent) and fertilizers (38 percent).

Taken together, commodities rose by 43 percent. If energy and precious metals are excluded, they declined by 16 percent. Assuming that an average inhabitant of the world spent exactly the same fraction of her income on the World Bank's list of commodities in 1960 and in 2015, she would be better off under either scenario, since her income rose by 163 percent over the same time period.

More

Reason

January 12, 2016

Last week, the World Bank updated its commodity database, which tracks the price of commodities going back to 1960. Over the last 55 years, the world's population has increased by 143 percent. Over the same time period, real average annual per capita income in the world rose by 163 percent. What happened to the price of commodities?

Out of the 15 indexes measured by the World Bank, 10 fell below their 1960 levels. The indexes that experienced absolute decline included the entire non-energy commodity group (-20 percent), agricultural index (-26 percent), beverages (-32 percent), food (-22 percent), oils and minerals (-32 percent), grains or cereals (-32 percent), raw materials (-32 percent), "other" raw materials (-56 percent), metals and minerals (-4 percent) and base metals (-3 percent).

Five indexes rose in price between 1960 and 2015. However, only two indexes, energy and precious metals, increased more than income, appreciating 451 percent and 402 percent respectively. Three indexes increased less than income. They included "other" food (7 percent), timber (7 percent) and fertilizers (38 percent).

Taken together, commodities rose by 43 percent. If energy and precious metals are excluded, they declined by 16 percent. Assuming that an average inhabitant of the world spent exactly the same fraction of her income on the World Bank's list of commodities in 1960 and in 2015, she would be better off under either scenario, since her income rose by 163 percent over the same time period.

More

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)